Französisches Gesetz über illegale Online-Inhalte für verfassungswidrig erklärt: Was die EU daraus lernen sollte

Am 18. Juni 2020 erklärte das französische Verfassungsgericht die Schlüsselbestimmungen des Avia-Gesetzes für verfassungswidrig. Das Gesetz zur Bekämpfung von terroristischen Inhalten und Hatespeech im Internet war im Mai verabschiedet worden – trotz massiver Kritik von Vertretern der digitalen Wirtschaft und Zivilgesellschaft sowie der Europäischen Kommission. Das Verfassungsgericht entschied, dass das Gesetz gegen die Meinungsfreiheit verstoße und nicht mit der französischen Verfassung vereinbar sei.

Das Urteil des Gerichts ist einen großer Sieg für die digitale Meinungs- und Redefreiheit, nicht nur in Frankreich, sondern möglicherweise in ganz Europa. Das Urteil des Verfassungsgerichts wird aller Wahrscheinlichkeit nach einen großen Einfluss auf zukünftige Gesetzesvorschläge haben, die sich mit der Regulierung von Onlineinhalten befassen, wie die Verordnung zur „Verhinderung der Verbreitung terroristischer Inhalte im Internet“ (TERREG-Verordnung), die derzeit in der EU verhandelt wird (letzter öffentlicher Entwurf hier).

Wir veröffentlichen daher eine englische Übersetzung des Urteils (siehe unten).

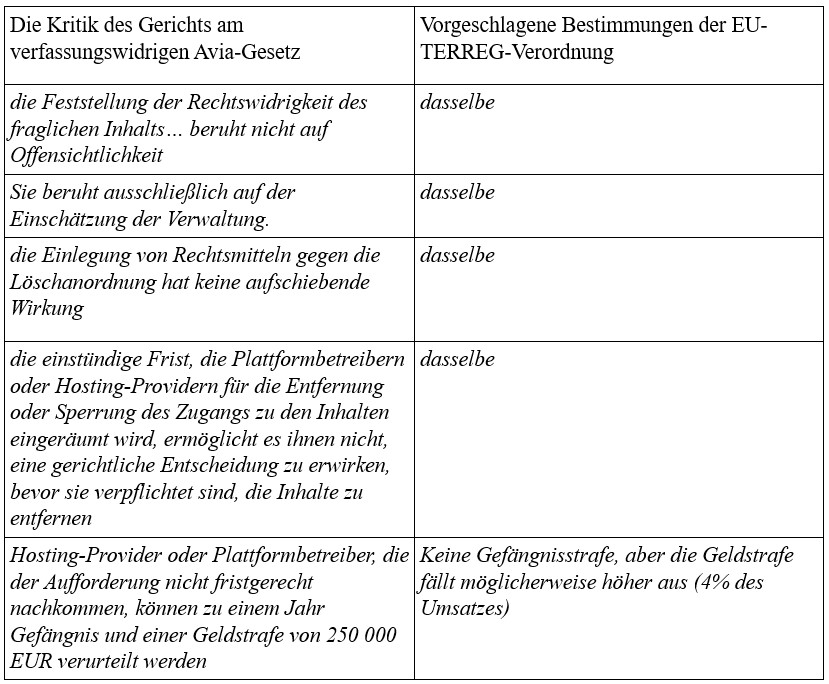

Außerdem habe ich die in der TERREG-Verordnung gelanten Löschanordnungen mit dem verglichen, was das französische Verfassungsgericht als Grundrechtsverletzung betrachtet hat (siehe Abs. 7 des Urteils). Davon ausgehend ist es wahrscheinlich, dass auch TERREG als Verstoß gegen die Grundrechte fallen könnte.

Decision No 2020-801 DC of 18 June 2020

Law on combating hate content on the internet

[Partial non-conformity]

In accordance with the conditions laid down in the second paragraph of Article 61 of the Constitution, the law on combating hate content on the internet WAS REFERRED TO THE CONSTITUTIONAL COUNCIL under reference No 2020-801 DC, on 18 May 2020, by […]

Having regard to the following texts:

- the Constitution;

- Order No 58-1067 of 7 November 1958 laying down an organic law on the Constitutional Council;

- Directive 2000/31/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2000 on certain legal aspects of information society services, in particular electronic commerce, in the Internal Market (‘Directive on electronic commerce’);

- Law No 86-1067 of 30 September 1986 on freedom of communication;

- Law No 2004-575 of 21 June 2004 on trust in the digital economy;

Having regard to the Government’s observations, registered on 10 June 2020;

And having heard the rapporteur;

THE CONSTITUTIONAL COUNCIL HAS ESTABLISHED THE FOLLOWING:

1. The applicant Senators have referred the Law on combating hate content on the internet to the Constitutional Council. They contest the constitutionality of certain provisions of Articles 1 and 7, and Articles 4, 5 and 8 of the Law at issue.

– On certain provisions of Article 1:

. Paragraph I

2. Article 1(I) of the Law at issue amends Article 6-1 of Law No 2004-575 of 21 June 2004, which provides that the administrative authority may ask a hosting provider or publisher of an online communication service to remove certain terrorist or child sexual abuse content and, if this is not done within 24 hours, allows the administrative authority to notify the list of addresses with offending content to the internet service providers, who must disable access to them without delay. Article 1(I) of the Law at issue reduces to one hour the time limit for publishers and hosting providers to remove the content notified by the administrative authority and, in the event of a failure to comply with that obligation, provides for a penalty of one year’s imprisonment and a fine of EUR 250 000.

3. The Senators contend that those provisions, which were adopted at a further reading of the bill, were adopted in breach of Article 45 of the Constitution. They further allege that the paragraph concerned, the purpose of which is to transpose Directive 2000/31/EC (the ‘e-Commerce Directive’ mentioned above), is manifestly incompatible with that directive. They also maintain that the resulting restriction on the freedom of expression and communication is disproportionate owing to the lack of sufficient safeguards. They contend, furthermore, that the provisions concerned would impose excessive burdens on all publishers and hosting providers and would thus breach the principle of equality vis-à-vis government encumbrances.

4. Article 11 of the Declaration of Human and Civic Rights of 1789 reads: ‘The free communication of ideas and of opinions is one of the most precious rights of man. Any citizen may therefore speak, write and publish freely, except what is tantamount to the abuse of this liberty in the cases determined by Law.’ Given the current situation with regard to means of communication, and bearing in mind the widespread development of online public communication services and their importance for participation in democratic life and the expression of ideas and opinions, that right implies the freedom to access such services and to use them as means of expression.

5. Article 34 of the Constitution provides that: ‘Statutes shall determine the rules concerning: civic rights and the fundamental guarantees granted to citizens for the exercise of their civil liberties’. On that basis, the legislature may adopt rules governing the exercise of the right of free communication and of the freedom to speak, write and publish. The legislature may also, therefore, adopt provisions aimed at preventing abuses in the exercise of the freedom of expression and communication which breach public order and impinge upon the rights of third parties. The freedom of expression and communication is all the more precious, however, given that its exercise is a requirement of democracy and is one of the safeguards in place to ensure that other rights and freedoms are upheld. Restrictions on the exercise of that freedom must therefore be necessary, appropriate and proportionate to the objective sought.

6. The dissemination of pornographic images depicting minors, on the one hand, and the incitement or condoning of acts of terrorism, on the other, constitute abuses of the freedom of expression and communication that are serious breaches of public order and seriously impinge upon the rights of third parties. It was the legislature’s intention to prevent such abuses by requiring publishers and hosting providers to remove, at the request of the administration, content that the latter considers to breach Article 227-23 and Article 421-2-5 of the Penal Code.

7. First, the determination of the unlawful character of the content in question, however, is not based on the manifest nature of that content. It is based solely on the assessment of the administration. Second, the lodging of an appeal against the request for removal has no suspensive effect, and the one-hour time limit that publishers or hosting providers are given to remove or disable access to the content does not enable them to obtain a court decision before they are obliged to remove the content. And third, hosting providers or publishers who fail to comply with the request within the time limit could be sentenced to a year in prison and fined EUR 250 000.

8. Here, then, the legislature is restricting the freedom of expression and communication in a way that is not appropriate, necessary and proportionate to the objective sought.

9. Article 1(I) of the Law is therefore unconstitutional. There is no need to consider the other objections.

. Paragraph II

10. Article 1(II) of the Law at issue inserts a new Article 6-2 into Law No 2004-575 of 21 June 2004, making certain online platform operators criminally liable if they fail to remove or disable access to unlawful hate content, or unlawful content of a sexual nature within 24 hours.

11. The Senators contend, first, that paragraph II, the purpose of which is to transpose Directive 2000/31/EC, is manifestly incompatible with that directive. They maintain, furthermore, that the penalty for failing to remove the offending content is contrary to the freedom of expression and communication. In this regard, they contend that it is unnecessary to restrict that freedom in this way as there are many legislative provisions in place that make it possible to prevent and punish the dissemination of such content. They maintain that such restrictions would also be disproportionate in that the limited amount of time operators are given to remove the content, coupled with the difficulties involved in establishing whether the comments concerned are manifestly unlawful, will result in them simply removing all content that has been identified as potentially unlawful. The Senators also take the view that the provisions concerned breach the principle that all offences should be strictly defined by law. In their view, the new offence is not defined clearly enough, as it may be the result of mere negligence on the part of the operator, who would have to undertake complex legal classification work to identify unlawful comments. Finally, various categories of criminal law can be used to prosecute the failure to remove hate speech or content of a sexual nature, and the Senators maintain that therefore there is a breach of the principles of necessity of penalties and equality before criminal law.

12. Pursuant to the provisions at issue, certain online platform operators whose activities exceed thresholds laid down by decree are to be held criminally liable if they do not remove or disable access to any content notified to them when that content might manifestly fall within the scope of certain criminal law categories listed in those provisions. The following offences are concerned: condoning the commission of certain crimes; incitement to discrimination, hatred or violence against a person or group of people on the grounds that they belong, or do not belong, to a particular ethnic group, nation, race or religion, or on the grounds of their gender, sexual orientation, gender identity or disability, or incitement to discrimination against persons with disabilities; challenging a crime against humanity as defined in Article 6 of the Charter of the International Military Tribunal annexed to the London Agreement of 8 August 1945 and committed either by members of an organisation declared criminal under Article 9 of that Charter, or by a person found guilty of such crimes by a French or international court; denying, undermining or trivialising in an extreme manner the existence of a crime of genocide, of a crime against humanity other than those already referred to, of a crime of enslaving a person or exploiting an enslaved person, or of a war crime when that war crime has resulted in a conviction handed down by a French or international court; insulting a person or a group of people on account of their origin or on the grounds that they belong, or do not belong, to a particular ethnic group, nation, race or religion, or insulting a person or group of people on the grounds of their gender, sexual orientation, gender identity or disability; sexual harassment; transmitting an image or representation of a minor when that image or representation is of a pornographic nature; the direct provocation of acts of terrorism or the condoning of such acts; the dissemination of a message of a pornographic nature likely to be seen or received by a minor.

13. In adopting these provisions, the legislature wished to prevent the commission of acts that cause major disruption to public order and to prevent the dissemination of statements praising such acts. Their intention was to put a stop to abuses in the exercise of the freedom of expression that disrupt public order and impinge upon the rights of third parties.

14. First, however, once a person has reported unlawful content to an operator, specifying their identity, the location of the content and the legal grounds on which it is manifestly unlawful, the obligation to remove that content falls on the operator. That obligation is not subject to prior judicial intervention, nor is it subject to any other condition. It is therefore up to the operator to examine all the content reported to it, however much content there may be, in order to avoid the risk of incurring penalties under criminal law.

15. Second, while it is up to online platform operators to remove only content that is manifestly unlawful, the legislature has relied on a variety of offences categorised in criminal law to justify the removal of such content. Moreover, the operator’s assessment should not be limited to the grounds set out in the notification. It is therefore up to the operator to examine the reported content in the light of all these offences, even though the constituent elements of some of them may present a legal technicality or, in the case of press offences, in particular, may require assessment in the light of the context in which the content at issue was formulated or disseminated.

16. Third, the legislature has obliged online platform operators to remove the content concerned within 24 hours. However, given the difficulties involved in establishing that the reported content is manifestly unlawful in nature, as referred to above, and the risk of numerous notifications that may turn out to be unfounded, such a time limit is extremely short.

17. Fourth, while parliamentary proceedings show that the legislature’s intention was to establish, in the last subparagraph of the new Article 6-2(I), a ground for exempting online platform operators from liability, that ground – according to which ‘the intentional character of the infringement … may result from the lack of a proportionate and necessary examination of the content reported’ – is not drafted in terms that allow the scope of the exemption to be determined. No other specific ground for an exemption from liability is provided for, such as multiple notifications being made at once.

18. Finally, failure to meet the obligation to remove or disable access to manifestly unlawful content is punishable by a fine of EUR 250 000. What is more, criminal penalties are incurred for each failure to remove content, with no account being taken of whether notifications are repeated.

19. In the light of the foregoing, therefore, taking into account the difficulties involved in establishing, within the prescribed time limit, that the content reported is manifestly unlawful in nature, the penalty incurred from the first infringement and the lack of any specific ground for exemption from liability, the provisions that are being challenged can only encourage online platform operators to remove content notified to them, whether or not it is manifestly unlawful. The provisions therefore restrict the exercise of freedom of expression and communication in a manner that is not necessary, appropriate and proportionate. Article 1(II) is therefore unconstitutional, and there is no need to consider the other objections.

20. The same applies to Article 3 of the Law at issue, which supplements the new Article 6-2 of Law No 2004-575 of 21 June 2004, to the words ‘and in the penultimate subparagraph of paragraph I of Article 6-2 of Law No 2004-575 of 21 June 2004 on trust in the digital economy’ appearing in the second subparagraph of Article 10 and to point 1 of Article 12, which are inseparable therefrom.

– On Articles 4, 5, 7, 8, 9 and 18:

21. Articles 4, 5, 7, 8, 9 and 18 lay down certain obligations relating to the monitoring of unlawful content to which certain operators may be subject, as well as the arrangements according to which they enter into force.

22. The senators contend that Articles 4, 5 and 7, the purpose of which is to transpose Directive 200/31/EC, are manifestly incompatible with that directive. They also maintain that the penalty provided for in Article 7 – which the Conseil supérieur de l’audiovisuel (France’s audiovisual media regulator) can impose on operators who fail to fulfil their obligations – is a breach of Article 16 of the Declaration of Human and Civic Rights of 26 August 1789, as insufficient guarantees are provided with regard to the amount concerned and the risk that administrative penalties imposed in several EU Member States for the same offence could accumulate. Lastly, the Senators maintain that Article 8, which authorises the administration to ask certain operators to prevent access to sites with content already deemed unlawful either constitutes incompétence négative (i.e. the administration has denied itself powers unlawfully) or is not provided for by law. They maintain that Article 8 also restricts the freedom of expression and communication because it fails to provide sufficient guarantees.

23. There is no need to consider these objections, however, because, first of all, Article 4 inserts a new Article 6-3 into Law No 2004-575 of 21 June 2004, which lays down a list of the obligations to be met by the operators referred to in the first and second subparagraphs of the new Article 6-2 of that Law, created by Article 1(II) of the Law at issue for the purpose of combating the dissemination online of the content referred to in the first subparagraph of Article 6-2. Article 5 adds to that list. Several of those obligations are directly linked to the conditions for implementing the obligation to remove certain content as laid down in Article 1(II). Since that paragraph (II) has been declared unconstitutional, the same applies to Articles 4 and 5 of the Law at issue.

24. Second, Article 7(I) inserts into Law No 86-1067 of 30 September 1986 a new Article 17-3 laying down the powers of the Conseil supérieur de l’audiovisuel (the audiovisual media regulator) to ensure or encourage compliance with the provisions laid down in Articles 6-2 and 6-3 of Law No 2004-575 of 21 June 2004, created by Article 1(II) and Articles 4 and 5 of the Law at issue. Article 7(II) amends, for the same purposes, Article 19 of Law No 86-1067 of 30 September 1986. Since Article 1(I) and (II) and Articles 4 and 5 have been declared unconstitutional, the same applies to the first two paragraphs of Article 7 of the Law at issue, and to the remaining provisions of Article 7, which are inseparable from the first two paragraphs. The same applies to Article 19(II), which is inseparable from Article 7.

25. Third, Article 8 of the Law at issue inserts into Law No 2004-575 of 21 June 2004 a new Article 6-4 laying down the conditions under which the administration may ask an operator to disable access to a site with content that a court has deemed to constitute offences within the meaning of Article 6-2(I), first subparagraph, as created by Article 1(II) of the Law at issue. The operator concerned is then placed on a list kept by the administration. Since Article 1(II) has been declared unconstitutional, the same applies to Article 8 and to Article 9, which, because it governs relations between certain advertisers and the operators included on the list kept by the administration, is inseparable from Article 8.

26. Finally, since Articles 4, 5 and 7 have been declared unconstitutional, the same applies to the references to those articles in Article 18, which lays down the arrangements concerning entry into force.

– The position with regard to other provisions in the Law at issue:

27. The second sentence of Article 45 of the Constitution reads: ‘Without prejudice to the application of Articles 40 and 41, all amendments which have a link, even an indirect one, with the text that was tabled or transmitted, shall be admissible on first reading.’ The Constitutional Council must declare unconstitutional any provisions introduced in breach of that procedural requirement. In this case, the Constitutional Council is not ruling on whether the content of such provisions meets other constitutional requirements.

28. The Law at issue started life as a bill tabled in the Assemblée nationale on 20 March 2019. The bill as first tabled contained eight articles. Article 1 made certain online platform operators liable to penalties imposed by the Conseil supérieur de l’audiovisuel (the audiovisual media regulator) if they failed to remove certain manifestly unlawful content within 24 hours. Article 2 amended the arrangements for reporting unlawful content to hosting providers. Article 3 required online platform operators to make available to the public information on the remedies available, in particular to victims of the unlawful content referred to in Article 1. Article 4 entrusted the Conseil supérieur de l’audiovisuel with the task of monitoring action to combat the dissemination of unlawful content on the internet. Article 5 made it mandatory for online platform operators to have a legal representative in France and increased the fine imposed in the event of a failure to meet existing obligations. Article 6 gave the administrative authority the power to issue directions to prevent access to content that duplicates content outlawed by a court ruling. Article 7 stipulated that an annual report should be submitted to the French Parliament on the implementation of the law and the resources devoted to combating unlawful content, including as regards education, prevention and victim support. Article 8 concerned the financial admissibility of the bill.

29. Article 11 of the Law at issue amends Article 138 of the Code of Criminal Procedure and Article 132-45 of the Penal Code for the purposes of adding to the list of obligations likely to be imposed in the context of a judicial review or suspended sentence by prohibiting the sending of messages, including electronic ones, to the victim. These provisions were introduced at first reading. They are applicable to any judicial review and any suspended sentence, regardless of the offence in question. They are not connected, even indirectly, with Article 1 of the initial text that introduced an administrative penalty for failure to remove certain unlawful content published online. And nor are they connected with Article 3 of the initial text, which laid down measures concerning the provision of information to those affected by the content, or with any of the provisions set out in the bill tabled in the Assemblée nationale.

30. Points 2 and 3 of Article 12 amend the provisions of Article 510 and 512 of the Code of Criminal Procedure on appeals against decisions in criminal matters handed down by a court presided over by a single judge. These provisions were introduced at first reading. They are not connected, even indirectly, with the provisions laid down in the bill tabled in the Assemblée nationale.

31. In this instance the Constitutional Council is not ruling on whether the content of the provisions concerned meets other constitutional requirements. However, because the provisions were adopted by means of a procedure that was inconsistent with the Constitution, they are therefore unconstitutional.

– On other provisions:

32. The Constitutional Council did not raise of its own motion any other issues relating to conformity with the Constitution. Therefore it has taken no decision on the constitutionality of any provisions other than those considered in this decision.

THE CONSTITUTIONAL COUNCIL DECIDES AS FOLLOWS:

Article 1. – The following provisions of the Law on combating hate content on the internet are unconstitutional:

- paragraphs I and II of Article 1 thereof;

- Article 3 thereof;

- Article 4 thereof;

- Article 5 thereof;

- Article 7 thereof;

- Article 8 thereof;

- Article 9 thereof;

- the words ‘and in the penultimate subparagraph of paragraph I of Article 6-2 of Law No 2004-575 of 21 June 2004 on trust in the digital economy’ in the second subparagraph of Article 10 thereof;

- point 1 of Article 12 thereof;

- the words ‘4 and 5, and I, II and III of Article 7’ in the first sentence of Article 18 thereof, and the second sentence of that article;

- paragraph II of Article 19 thereof;

- Article 11 thereof and points 2 and 3 of Article 12 thereof.

Article 2. – This decision shall be published in the Official Journal of the French Republic.

Decision taken by the Constitutional Council at its sitting of 18 June 2020, at which the following were present: Laurent FABIUS (President), Claire BAZY MALAURIE, Valéry GISCARD d’ESTAING, Alain JUPPÉ, Dominique LOTTIN, Corinne LUQUIENS, Jacques MÉZARD, François PILLET and Michel PINAULT

Published on 18 June 2020.

OJFR 156, 25 June 2020, text No 2

ECLI: FR : CC : 2020 : 2020.801.DC

Comments